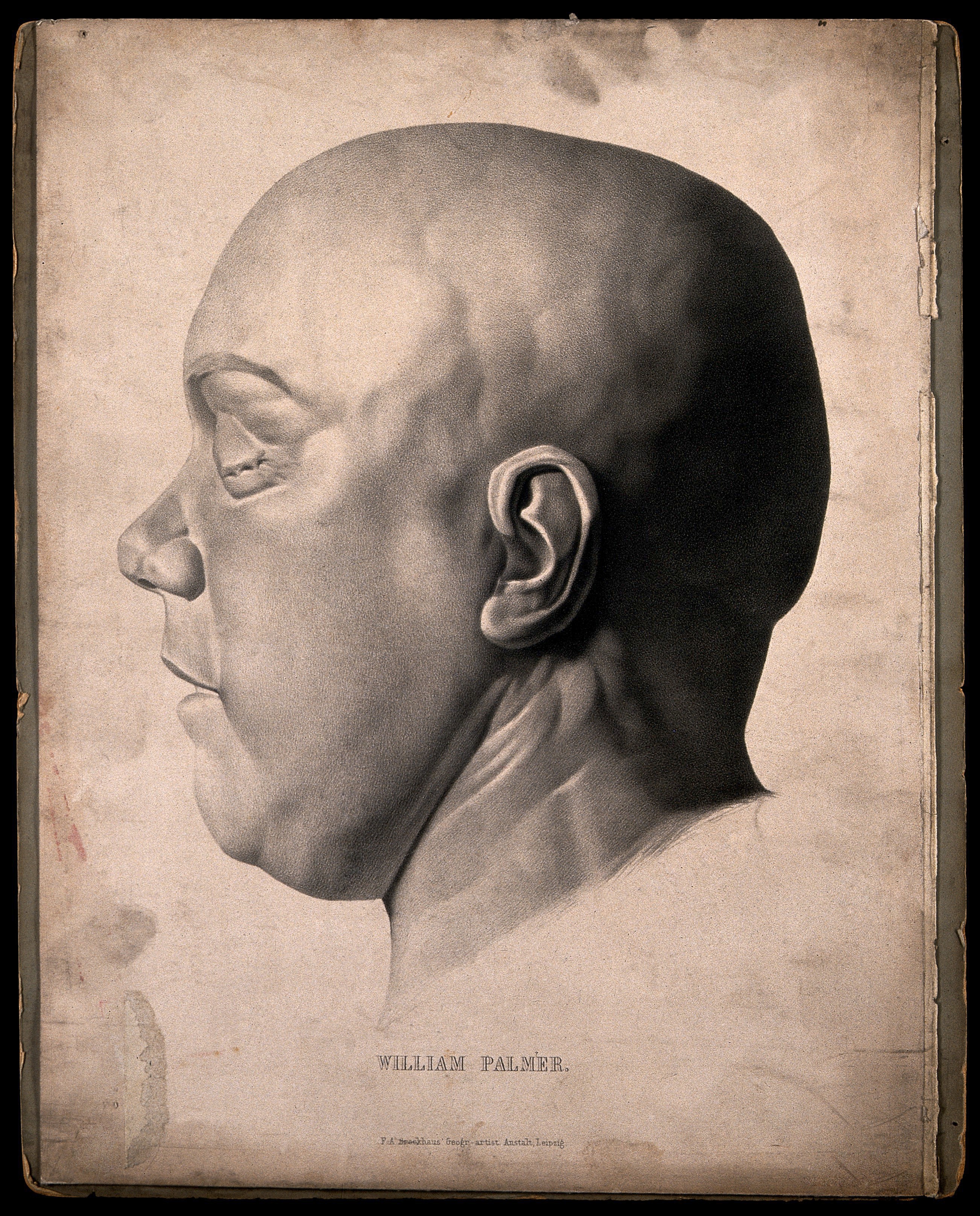

The weather on the morning of Saturday 14 June 1856 was wet with persistent drizzle, but it did not deter the crowds gathering in Stafford. From the early hours, thousands of people had been arriving on foot and by train, and an air of eager anticipation was building. Was Queen Victoria or another famous dignitary visiting? Or was a travelling fair or circus due in town? In fact, none of these explanations were correct; the crowds were waiting to witness justice meted out to convicted murderer, Dr William Palmer, dubbed by the press the ‘Prince of Poisoners’. In an age before cinema, the Victorians loved a spectacle and the drama of a hanging was certainly that.

Until the 1820s, there were some four hundred criminal offences which carried the death penalty including picking someone’s pocket of anything worth one shilling (5p) or more and stealing anything worth £2. The number of capital offences was gradually reduced by successive governments until 1861 when the Offences Against the Persons Act specified that only wilful murder and treason were punishable by death.

From the mid-nineteenth century, even when the death sentence was passed on a convicted murderer, there was still a chance that he or she could be reprieved and instead spend the rest of his or her life in penal servitude. In such cases, the prisoner might have to wait several weeks to know whether he or she was to live or die.

For Dr William Palmer, there was to be no reprieve. On 27 May 1856, he was convicted of murdering his friend, John Parsons Cook by administering strychnine in November 1855 in Rugeley, Staffordshire. Palmer was constantly in debt and regularly gambled on the horses. On 13 November at the Shrewsbury Races, Cook had won about £3,000 but the following day, Palmer lost heavily on another horse. Cook became ill after having a meal with Palmer that evening at the Raven Inn, Shrewsbury. The next day, Cook was slightly better so he and Palmer returned to Rugeley where Cook took a room at the Talbot Arms opposite Palmer’s house.

Over the following days, Cook continued to be sick and Palmer regularly visited his friend to check up on him. On 19 November, Palmer took Cook’s betting books to obtain the various winnings on his behalf. Two days later, Palmer prescribed what he called ‘ammonia pills’ for Cook after which a ‘terrible scene’ ensued:

‘Wildly shrieking, the patient tossed about in fearful convulsions; his limbs were so rigid that it was impossible to raise him, though he entreated that they would do so, as he felt that he was suffocating. Every muscle was convulsed; his body bent upwards like a bow; they turned him over on his left side; the action of the heart gradually ceased; and he was dead.’

The Illustrated Times (2 February 1856)

A coroner’s inquest followed and a botched post-mortem was held in which Palmer himself interfered with the examination; the resulting samples were of such poor quality that the toxicologist, Dr Alfred Swaine Taylor, could not make use of them. A second post-mortem was ordered and although no traces of poison were found, Dr Taylor still believed Cook had been poisoned. On 15 December, the jury at the inquest stated that the deceased had ‘died of poison wilfully administered to him by William Palmer’. Palmer was duly arrested and charged with Cook’s murder.

In the weeks and months after Cook’s death, the newspapers printed various rumours and allegations about Palmer and other possible victims he may have poisoned, including his wife, brother, mother-in-law and four infant children. This trial by the press effectively found him guilty before he had even stepped inside a court. It was felt that local prejudice against him was very strong in the community in which the crime was committed and it was highly unlikely that a jury could be unbiased. As a result, Palmer’s twelve-day-trial in May 1856 took place at the Central Criminal Court (the ‘Old Bailey’) in London, where he was found guilty.

Dr Palmer’s execution was scheduled to take place at 8am on Saturday 14 June outside Stafford Prison. As the trial had attracted so much public interest, huge crowds were expected that rainy morning to witness the hanging. The Times reported that ‘Balconies and platforms were erected on several of the housetops and in almost every imaginable place commanding a view of the spectacle and the windows of the houses in the front and near the scaffold had their full complement of eager spectators. The express train and others from London on Friday night brought down a great number of well-dressed persons…the crowds…kept constantly arriving during the night by railway and other means of conveyance from the adjacent towns for 50 miles around, including the Pottery districts, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Walsall, Tipton and the rest of what is called “the black country”. The great bulk of the people were young men and lads, labourers and artisans, thousands of whom had left their ordinary occupations and travelled many miles to witness the spectacle…’

Interestingly, the Staffordshire Advertiser, the local newspaper best placed to report on the execution, was at pains to point out the incorrect descriptions of the crowd’s behaviour that appeared in other publications, believing that ‘some of the reports were written by anticipation, which is the only excuse we can find for their strange inaccuracy’. One account had claimed that ‘as soon as Palmer appeared on the scaffold, there was a universal shout of execration. From every part of the dense multitude there issued shrieks, groans and curses, mingled with cries expressing indignant abhorrence.’ Another described the crowd as ‘extremely indecorous and blasphemous’ while yet another said that ‘deep sympathy and pity’ was the predominant feeling of the spectators. The Staffordshire Advertiser was adamant that none of these descriptions were accurate. It did, however, approve of the report in The Times, which was ‘given with much care and correctness’ although special constables were not deployed as had been stated.

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser, on the morning of the execution, ‘people were gradually admitted within the barriers, and the rain helped to keep the crowd thinner than otherwise would have been the case… Precautions were taken by having ladders within the lower walls outside the gaol to remove any who might faint, and the necessity for this was soon evident, as instances of fainting presented themselves at an early hour.’ The newspaper went on to state there were between 30,000 and 35,000 people in the crowd but no more than one in twelve were females ‘none being admitted within the barriers’. The spectators appeared to be ‘chiefly respectable working people and tradesmen, and not to any large extent “swells” and low blackguards. Their demeanour was highly decorous, and the patience with which they awaited the period fixed for the execution was really remarkable. So far as our observation went, no oath was uttered, and the hoarse murmur of voices never rose above the accumulated hum of multitudes speaking in an ordinary tone.’

At seven minutes to eight, the minute bell gave the first toll, announcing to the crowd the departure of the melancholy procession from the cell of the condemned convict. At once

‘the hoarse murmur of the crowd arose into a loud buzz of excited expectation, which the multitude of voices swelled into a roar. A cry of “hats off” was raised…the noise subsided and a respectful, if not solemn, silence succeeded. Every face was eagerly upturned to catch the first glimpse of the wretched culprit. Here and there there was a laugh, but popular feeling was against it, and at the rebukes of the more serious it ceased. The condemned man ascended the steps with a quick, firm step, and placed himself on the centre of the drop, with his face towards the Gaol-square…He never flinched or shuddered as the executioner placed the rope around his neck and drew the white cap over his face. That done, the bolt was immediately withdrawn, and the drop fell. Being a stout heavy man he never struggled at all; a few convulsive twitchings of his arms and legs alone ensued, and after a few seconds his limbs hung motionless in death. The crowd did not shout or yell as do often such gatherings at the Old Bailey, but behaved with the utmost decorum, and in a few minutes after the drop fell began quietly to disperse. The body, after hanging an hour, as prescribed by law, was cut down and removed.’

Reports of reactions after previous hangings tend to suggest that the crowd would have been disappointed by Palmer’s lack of struggle and relatively quick death. Yet the Staffordshire Advertiser makes no mention of this. It also appears that the well-organised policing of the event prevented any deaths from suffocation among the spectators, as had happened at Newgate in 1807 when 27 people died and 70 needed hospital treatment. At William Palmer’s execution, it seems that the crowd was unusually well-behaved. Such events had a reputation for drunknenness and crime such as pickpocketing, but the Staffordshire Advertiser had not heard ‘of a single case in which the police have had to make an arrest, or a complaint of any theft having been committed, and no accident whatever occurred’.

Public executions were originally designed to act as a deterrent to would-be criminals and a moral lesson, and they were always well-attended. By the 1860s, for the upper- and middle-classes, it became distasteful to witness executions and legislation was introduced to ban public hangings. The last public execution in England took place in 1868. After this date, executions were carried out in private behind closed doors in prison. Crowds still gathered in large numbers outside to see the black flag hoisted above the prison, a sign that the sentence had successfully taken place.

To read more Victorian newspaper reports about criminal cases in the UK, visit the British Newspaper Archive (affiliate link). For further information about the history of capital punishment in the UK, see Richard Clark’s excellent Capital Punishment website. To find out more about the William Palmer case, visit Dave Lewis’s meticulously researched William Palmer the infamous Rugeley poisoner website.

France held its last public guillotine execution in 1939.

Peter

LikeLike

Thanks for pointing this out, Peter.

LikeLike

Very nnice post

LikeLike

Glad you liked it, Annie.

LikeLike