If they had money in their pockets, the Victorians could find plenty of places to eat out, especially in the towns and cities. From rough-and-ready chop houses and public houses, elegant tea rooms and refreshment rooms, through to oyster bars and high-class restaurants, there was a plethora of eateries for different social classes and budgets.

In the mid-nineteenth century, women were a rare sight in restaurants. The American Stranger’s Guide to London and Liverpool at Table (1859) highlighted that in London and other cities, it was difficult to find restaurants where women could dine: ‘It is true that some have been opened where gentlemen may take their wives and daughters, but it has not yet become a recognised custom, although at Blackwall, Greenwich, Hampton Court, Windsor, Slough, Richmond, ladies are to be found as in the Parisan Cafes, and in London at ‘Verey’s’ in Pall Mall and Regent Street; but to give a private dinner with ladies, it is necessary to go to the ‘Albion’ or ‘London Tavern’ where nothing can exceed the magnificence of the rooms.’ By the 1880s, it had become acceptable for women and girls to eat out, even unaccompanied by men, and the male-dominated world of restaurants was no more.

For the middle classes, restaurants offering table d’hôte (set menus at a fixed price) were extremely popular. Pope’s Restaurant in Birmingham, called the ‘Vatican’ by its proprietor. offered table d’hôte between 5pm and 8.30pm for 3s 6d. The menu included olives stuffed with anchovies; soups (macaroni or hare); fish (boiled turbot and lobster sauce or fried eels); entrées (mutton cutlets and tomato sauce or sauti of rabbit); joints (roast gosling); game (partridge or wild duck); sweets (sweet omelette); savoury (devilled sardines on toast); and cheese and salad. It’s no wonder that indigestion remedies were part and parcel of daily life…

British restaurants were not known for serving high-quality food. In Notes on England (1872), the Frenchman Hippolyte Taine observed that:

‘excepting in the very best clubs and among continentalised English people, who have a French or Italian chef, [the cooking] is devoid of savour. I have dined, deliberately, in twenty different inns, from the highest to the lowest, in London and elsewhere: huge helpings of greasy meat and vegetable without sauce; one is amply and wholesomely fed, but one can take no pleasure in eating. The best restaurant in Liverpool cannot dress a chicken. If your palate demands enjoyment, here is a dish of pimentos, peppers, condiments, Indian vinegars: on one occasion I carelessly put two drops into my mouth. I might just as well have been swallowing a red-hot coal. At Greenwich, having had a helping of ordinary ‘white bait’, I helped myself to more but from another dish: it was a dish of curried whitebait – excellent for taking the skin off one’s tongue.’

By the 1890s, an increasing number of restaurants had developed a reputation for good food, and this even applied to eateries catering for customers lower down the social scale. According to the periodical Living London, Slaters’ in Piccadilly served lunches for ‘the people of modest incomes and half-an-hour to spare’. By the afternoon, it was frequented by ladies looking for tea after shopping, which had now become a leisure pursuit.

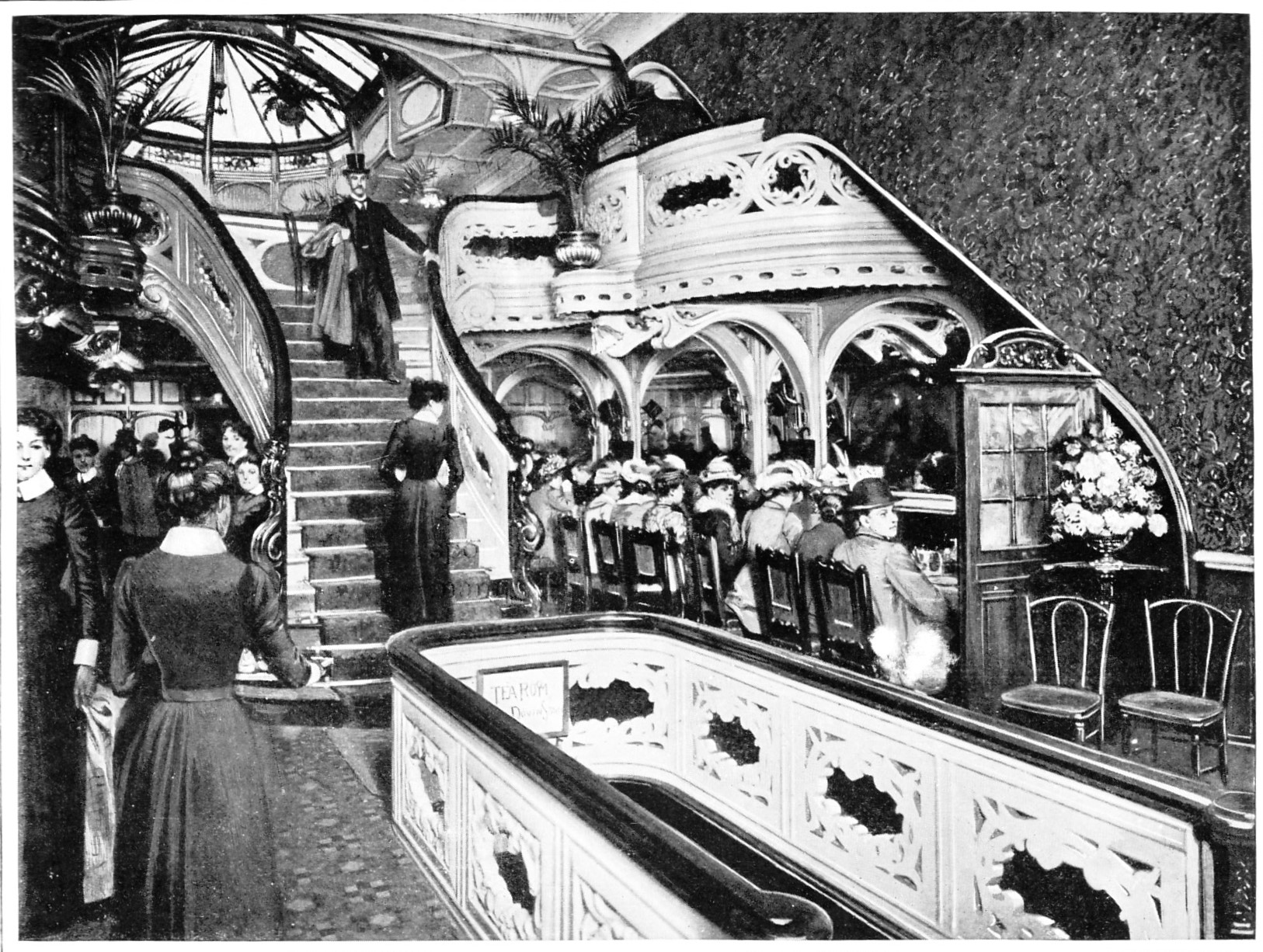

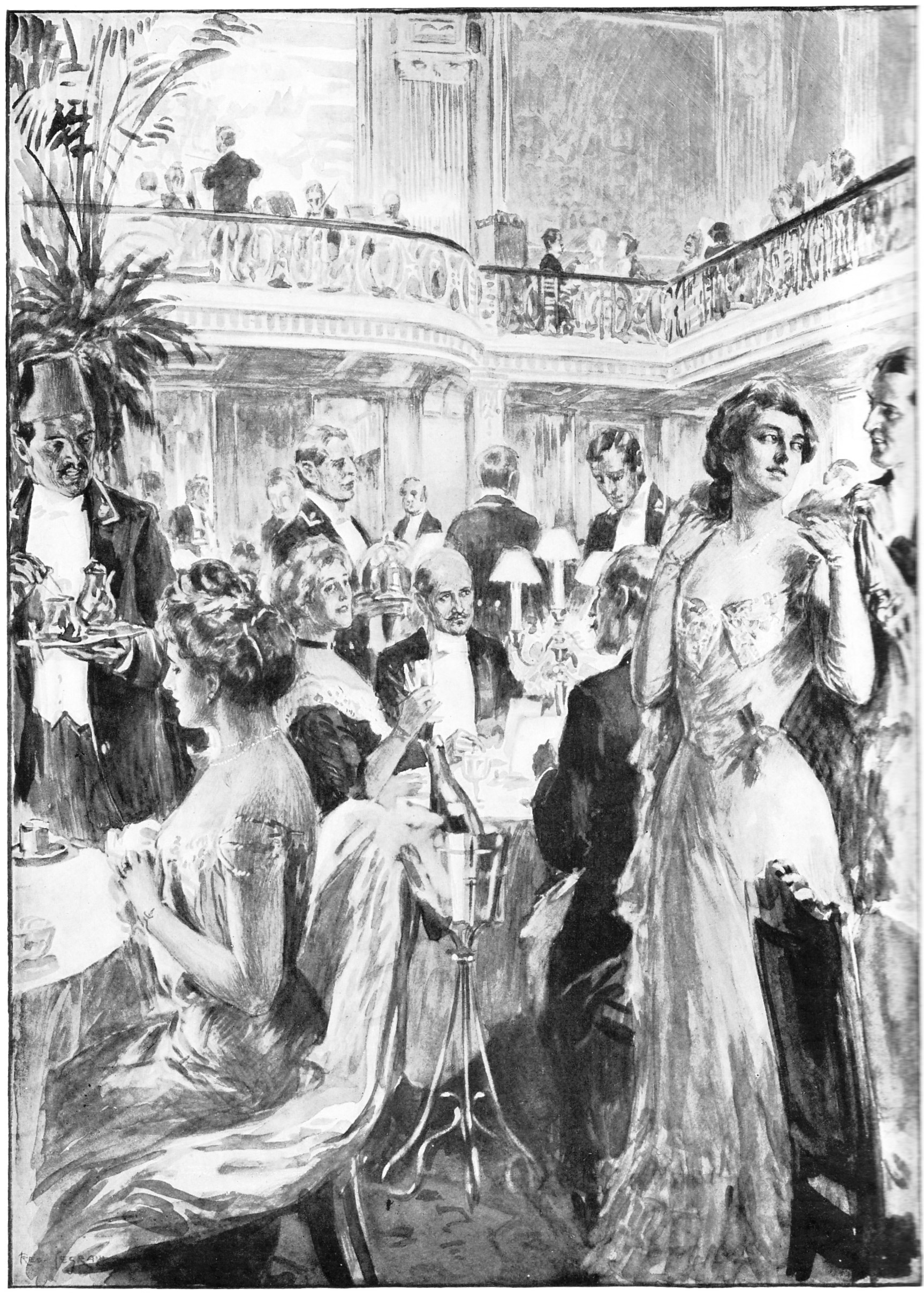

The Trocadero Restaurant in London is a good example of the new style of restaurant designed to appeal to a wide range of customers. It was opened in 1896 by J Lyons & Co, famous for its tea shops which had been introduced two years earlier. The Trocadero Restaurant was built on the site of the old Trocadero music hall. According to advertisements of the time, it offered ‘the finest cuisine in London’ with a choice of wines. On the ground floor was the entrance hall with its marble staircase, a palatial dining hall in the style of Louis XIV and a grand saloon with decorations from the Louis XV period. Upstairs, there was a large banqueting hall and ‘charming suites of rooms’ for private dining for small and large parties, as well as for weddings, receptions and balls. The orchestra of the Coldstream Guards performed every afternoon and evening when the restaurant first opened.

The managers at the Trocadero were deliberately targeting customers with many different budgets, offering ‘luxury with economy’. Lunches (à la carte and table d’hôte) were 3 shillings while dinners cost 5 shillings; 7s 6d or 10s 6d; suppers were 3s 6d. For those of more modest means, there was the popular half a crown (2s 6d) table d’hôte grill in the Flemish-style grill room.

You can find out more about the history of the Trocadero Restaurant, and the famous Trocadero music hall that preceded it, on the Arthur Lloyd website. There is also an amazing Trocadero Restaurant banquet book, owned by the Bennett family. Dating from the first few years of the restaurant’s existence, it lists hundreds of menus for banquets staged for individuals, companies and societies. Find out more at the Trocadero Banquet Book website.